Instruction

Instruction is learner-oriented, inclusive, designed to meet the communication and content needs of the particular group of learners, and informed by TESL theory and practice.

Click on a best practice for indicators that clarify how to meet the best practice.

Technical terms have been glossed for your convenience; hold your cursor over the gloss to see a definition.

Statements of Best Practice

For more detail on inclusion, see Best Practices for Anti-Racism, 2SLGBTQ+ Inclusion, Indigenization, and Supporting Learners with Diverse Learning Needs.

- The instructor creates a welcoming, supportive environment through any of the following:1

- A friendly, welcoming demeanor

- Enthusiasm

- Positive, encouraging feedback

- Use of humour

- Sincere concern for the wellbeing of the learners through consistent, respectful, compassionate, and non-judgmental communication

- Predictable routines

- Opportunities to move around, collaborate, and interact

- Opportunities to share one’s own story and experiences (i.e., learner accounts are not minimized, ignored, silenced, or deflected)

- A friendly, welcoming demeanor

- The instructor promotes an atmosphere of mutual respect through a selection of the following:

- At the beginning of a course, articulating (and encouraging learners to articulate) classroom expectations related to respectful interactions and inclusion of all learners in the class, with periodic reminders as needed. Explicit mention is made of race, ethnic identity, sexual orientation, gender identity, and gender expression.

- Welcoming a diversity of viewpoints

- Modelling respectful interactions with all learners, with deliberate use and modelling of inclusive language

- Ensuring that learners treat each other with respect; calling out disrespectful/discriminatory comments

- Presenting, and encouraging learners to use, the functions of language related to encouraging, complimenting, expressing polite agreement and disagreement, soliciting opinions, requesting clarification, etc.

- At the beginning of a course, articulating (and encouraging learners to articulate) classroom expectations related to respectful interactions and inclusion of all learners in the class, with periodic reminders as needed. Explicit mention is made of race, ethnic identity, sexual orientation, gender identity, and gender expression.

- The adult perspectives, intelligence, and wide range of skills and experiences that learners bring to class are acknowledged in ways such as the following:

- The objectives and purposes of classroom activities are explained.

- Learners share their prior knowledge of language and content.

- Learners share their experiences and expertise.

- Learners engage in tasks where they take on the role of “expert” and “teacher.”

- Other.

- The objectives and purposes of classroom activities are explained.

- Instructional activities are varied to address the individual differences of the learners and to maximize the potential for success of all learners (See also Best Practice #90 in Supporting Learners with Diverse Learning Needs):2

- Learning activities appeal to different ways of learning (e.g., visual, auditory, interactive, kinesthetic) as learners interact verbally, write, read, role-play, debate, sort, move, sing, etc.

- New language and information is presented in a variety of ways and in multiple formats (e.g., text, audio, visual aids, exploratory learning, field trips, games, verbal presentations reinforced by demonstrations, writing on the board, and handouts).

- Learners are provided with a variety of ways to demonstrate learning, present ideas, and communicate (e.g., individual and group projects/presentations, role-plays, written forums, audio forums, blogs, visual representations, quizzes, tests).

- Learners are encouraged to use their language skills to explore topics of personal interest.

- Learning activities appeal to different ways of learning (e.g., visual, auditory, interactive, kinesthetic) as learners interact verbally, write, read, role-play, debate, sort, move, sing, etc.

1 See TESOL (2003), Standard 3A4.

2 See TESOL (2003), Standard 3F.

- Course plans demonstrate direct connection to the objectives of the curriculum.

- Instructional activities reflect an appropriate balance of skills based on the learners’ needs and goals (e.g., listening and speaking are not neglected in favour of grammar and writing).

- Instructors formally or informally gather input from learners regarding a selection of the following:

- Interests

- Present and future needs and goals (as individuals; as members of families, communities, and workplaces)

- Proficiency levels in listening, speaking, reading, and writing

- Linguistic strengths and weaknesses (grammar, vocabulary, pronunciation)

- Learning preferences

- Special needs (literacy, learning disabilities)

- Other

- Interests

- Information from learners is used when planning instruction to identify appropriate goals and objectives, materials, approaches, themes, and tasks.

- If relevant, Skills for Success/Essential Skills (ES) resources are used to determine learners’ needs and interests related to workplace skills. (See Best Practices for Skills and Language for Work and related Resources for the Classroom)

- Feedback from learners regarding class content is solicited, both formally and informally.

- Changes to plans/content/materials/approaches are made in response to learner performance and feedback from learners.

- Materials reflect the breadth of learner experience and identity. (See 2SLGBTQ+ Inclusion, Anti-Racism, Supporting Learners with Diverse Learning Needs)

- Reading or listening materials meet the following criteria:

- They appeal to the interests and needs of the learners.

- They are authentic, including resources from community, workplace, or further education settings.

- They appeal to the interests and needs of the learners.

- The topics/themes about which learners speak or write are engaging, interesting, and relevant to the learners in a particular class.1

- Classroom activities and tasks reflect authentic communicative, real-world interactions and tasks that learners could expect to participate in, in specific community/social, work, or academic settings.

- If relevant, the Canadian Language Benchmarks–Essential Skills Comparative Framework, the Essential Skills (ES) Profiles, and other ES-referenced resources are used to ensure real-life authenticity of tasks and readings geared to learners’ workplace needs and goals. (See Skills and Language for Work References and PD Resources and Resources for the Classroom)

- In choosing language tasks, a selection of the following is considered:

- The present real-world needs of the learners

- The future goals of the learners

- The experience, skills, knowledge and interests of the learners

- The proficiency level of the class

- The requirements of a targeted workplace, profession, or field of study

- The objectives of the lesson/course

- The present real-world needs of the learners

- What is done in class reflects the real-life use to which language will be put.

- Listening, speaking, reading, and writing activities are related by topic, theme, or content.2

- Instruction is varied to appeal to different ways of learning. (See Best Practice #90 in Supporting Learners with Diverse Learning Needs)

- A principled approach is taken to the sequencing of learning activities, depending on the language level of the learners and the amount of scaffolding needed for the task:

- At times, instruction may begin with a focus on the communicative requirements of a task, followed by a focus on meaning and communication as learners complete a task, and end with reflection and a focus on form to improve accuracy and/or complexity.

- At other times, instruction may move from an initial focus on form, to practice activities that encourage learners to focus on that form while communicating, and finally to tasks where learners focus primarily on meaning while paying attention to a number of forms.

- And at other times, learner attention may alternate between a focus on form and a focus on meaning throughout the task cycle: in the preparation phase as they learn functional language and gather ideas; in the task phase as they complete tasks while attempting to incorporate new language; and in the post-task phase as they practice new forms and repeat a task.

- At times, instruction may begin with a focus on the communicative requirements of a task, followed by a focus on meaning and communication as learners complete a task, and end with reflection and a focus on form to improve accuracy and/or complexity.

- Learning task design reflects deliberate linking and springboarding; that is, each task works to “launch” the next task.

- There is a spiralling of instruction; curricular targets are “recycled” into new themes, contexts, and tasks.

1 Cultural universalities can be drawn on for thematic development (e.g., Family life; Health practices; Work and play; Fashion; Food and nutrition). See Donald E. Brown’s list of “human universals.”

2 See TESOL (2003), Standard 3E.

- Listening/reading texts and tasks are level-appropriate.

- Texts and tasks conform to the CLB descriptions for the level (CLB Features of Communication and Profiles of Ability, CCLB 2012).

- Readability statistics are consulted to ensure that texts are not overly complex for a level.

- Most of the vocabulary in a text is familiar to the learners (with a goal of 95% word recognition for general comprehension and 98% word recognition for fluent reading).

- Texts and tasks conform to the CLB descriptions for the level (CLB Features of Communication and Profiles of Ability, CCLB 2012).

- Pre-listening/reading activities, focused on the content, organization, genre, or language of the text, ensure that listening/reading materials are accessible, raise awareness of target language and skills, and provoke curiosity. Examples of pre-listening/reading activities are as follows:

- Vocabulary generation activities (e.g., word clouds, brainstorming, graphic organizers)

- Activities that introduce and make use of target language items (vocabulary, grammar) from the listening/reading (e.g., discussion questions, short readings with the target items, Quizlet activities)

- Predicting and questioning (e.g., based on a picture, an object, a title, a 30-second skim, listening to the introduction, watching a video without sound), followed by reading/listening to confirm predictions/answers

- Discussion of inference statements, then listening/reading to confirm answers

- Generating ideas through brainstorming and the use of graphic organizers

- Pre-teaching background information relevant to the content of the listening/reading

- Quizzes/surveys to raise awareness of content

- Activities to raise awareness of genre structure and text components

- Other

- Vocabulary generation activities (e.g., word clouds, brainstorming, graphic organizers)

- Learners interact with the texts in ways that develop particular listening or reading skills, depending on the needs and level of the class, such as the following:

- Skimming (listening/reading for the general idea)

- Scanning (listening/reading for specific information)

- Using knowledge of genre to make sense of text

- Recognizing signposts and organizational signals

- Stopping and predicting what will come next

- Analyzing the meaning of words and structures

- Identifying main ideas

- Making inferences (e.g., about purpose, audience, attitudes, opinions, relationships)

- Relating ideas to real life

- Integrating ideas from 2 or more sources

- Taking notes

- Summarizing

- Analyzing language

- Mimicking/shadow-reading

- Other

- Skimming (listening/reading for the general idea)

- Strategies for developing the above listening/reading skills, for improving listening/reading comprehension, and for improving reading speed are:

- Identified and discussed

- Demonstrated

- Practiced

- Reflected upon

- Identified and discussed

- Learners read/listen to access content to accomplish tasks that are meaning-focused and related to real life. For example, learners use information from a listening or reading text to do one or more of the following:1

- Follow instructions to do or make something

- Fix mistakes or errors in a text, illustration, table, etc.

- List and rank, sequence, or categorize

- Compare or contrast

- Advise/warn/convince

- Teach

- Debate

- Solve a problem

- Participate in a role-play or decision drama

- Plan a presentation

- Record a video

- Design a poster or infographic

- Prepare study questions

- Complete a form, table, graphic organizer, chart, notes, etc.

- Write a letter, memo, note, report, paragraph, research paper, etc.

- Answer comprehension questions

- Follow instructions to do or make something

- In both listening and reading, there are opportunities to build fluency. For example:

- Learners listen to or read the same text multiple times for different purposes and using different strategies (e.g., for purpose and audience, for the main idea, for the answer to a question, for details, to infer, to predict, to accomplish a task).

- Learners read and listen to simplified texts (e.g., graded readers, audios/videos with high-frequency vocabulary) to build fluency and familiarity with high-frequency vocabulary.

- Learners learn and use strategies for improving reading speed, for example:

- Timed readings

- Using apps such as Spreeder

- Repeated reading (e.g., learners read a passage for a minute, marking how far they read; they then reread multiple times, each time trying to read farther in a minute.)

- Learners develop fluent recognition of vocabulary as they listen to or read multiple texts on the same theme, content, or topic, or by the same author/speaker.

- Timed readings

- Learners listen to or read the same text multiple times for different purposes and using different strategies (e.g., for purpose and audience, for the main idea, for the answer to a question, for details, to infer, to predict, to accomplish a task).

- Extensive level-appropriate self-selected listening/reading for enjoyment is encouraged, both inside and outside of class.

1 Note: All of these (except perhaps the last 2) can be done collaboratively and orally, as learners negotiate in small groups, to ensure that oral skills are not ignored.

- Speaking/writing tasks are level-appropriate and authentic or authentic-like:

- Tasks conform to the CLB descriptions for the level (see CLB Features of Communication and Profiles of Ability).

- Tasks reflect learners’ real-world experience and/or the use of language in the real world.

- Tasks are deconstructed to determine the criteria for a level-appropriate performance of the task; these criteria are used to determine pre-task instruction and scaffolding, and to create peer-/self-/instructor-assessment tools.1

- Tasks conform to the CLB descriptions for the level (see CLB Features of Communication and Profiles of Ability).

- Prior to a speaking/writing task, learners receive sufficient input and scaffolding, enabling them to accomplish the task. This includes some of the following:

- Providing background knowledge related to the issues, ideas, content, or topic

- Teaching language related to the content of the task (e.g., in the form of vocabulary or a listening/reading text)

- Teaching functional language related to the genre/task (e.g., common language for emails; language for expressing opinions, clarifying, convincing, contrasting)

- Outlining discourse expectations related to the genre/task

- Using pre-task modelling (e.g., by the instructor, by analyzing a video/text, by having the whole class do a task prior to individuals doing the task)

- Generating or analyzing a peer-/self-assessment rubric; potentially using the rubric to evaluate good and poor models of the task prior to evaluating their own performance

- Allowing time to plan language and gather/organize ideas

- Providing background knowledge related to the issues, ideas, content, or topic

- The language that is targeted for focused instruction (e.g., vocabulary, grammar, functions) is based on any of the following:

- The objectives of the course

- The requirements of the task in terms of the content/topic and genre

- The level and needs of the learners

- The objectives of the course

- Speaking/writing tasks require learners to go beyond talking about language to using language. Tasks require learners to do the following:

- Consider purpose and audience

- Focus on both meaning and form

- Engage in real communication (i.e., an actual exchange of information, ideas, or opinions)

- Plan language use (i.e., incorporate newly learned language into the task)

- Accomplish a task with specific requirements and outputs that can be evaluated

- Consider purpose and audience

- In both speaking and writing, there are opportunities to build fluency, for instance, by repeating tasks but varying the time, audience, mode, topic, etc. For example, students can be asked to do the following:

- Give a 4-minute speech to one partner, then repeat it with a second partner in 3 minutes, then repeat it with a third partner in 2 minutes

- Take part in mingling and inside/outside circle activities for surveys, role-plays, and discussions

- Carry out tasks that require grouping and re-grouping (e.g., jigsaw activities)

- Give a presentation to a partner, then to a small group, then to the class

- Journal about a topic, writing a paragraph on that topic, and then incorporate that paragraph into a formal email

- Write a number of emails to invite people to different events

- Write an informal and a formal email to invite people to the same event

- Use formulaic sequences and lexical fillers in repetitive speaking tasks (e.g., surveys)

- Give a 4-minute speech to one partner, then repeat it with a second partner in 3 minutes, then repeat it with a third partner in 2 minutes

- In both speaking and writing, there are opportunities to increase language complexity and accuracy. For example, students can be asked to do the following:

- Attempt to use a target grammatical form (e.g., modals for suggestions) in a speaking or writing task

- Use 5 new vocabulary words in a speaking/writing task

- Edit writing for an aspect of grammar or punctuation that has previously been taught (e.g., making sure that past tense verbs are used; making sure sentences begin with capitals and end with periods)

- Attempt to use a target grammatical form (e.g., modals for suggestions) in a speaking or writing task

- Learners are provided with ample opportunities to practice their speaking/writing skills, both inside and outside of class.2

- Writing activities acknowledge the writing process and encourage peer involvement at different points throughout that process:

- Idea generating

- Organizing

- Drafting and re-drafting

- Revising and editing

- Idea generating

- Learners have the opportunity to engage in reflection and self-assessment (e.g., through “Did I…?” checklists and daily/weekly reflections).

- Learners receive timely feedback, for instance, through the following:

- Audio/video feedback (e.g., screencasting used to provide verbal and visual feedback on writing tasks; screencasting used to provide feedback at appropriate points on videoed tasks)

- Language instruction (grammar, functional language, pragmatics) and corrective feedback to the entire class regarding errors made by many in the class

- Specific, detailed, written feedback (e.g., using symbols to identify errors; providing correct forms)

- Identifying errors and having learners self-correct

- Identifying errors and providing links to relevant online resources

- Global feedback (e.g., “Edit this to make sure you use the simple past tense when you are talking about things that happened at a specific time in the past.”)

- Individual conferences where learners receive and negotiate feedback

- Audio/video feedback (e.g., screencasting used to provide verbal and visual feedback on writing tasks; screencasting used to provide feedback at appropriate points on videoed tasks)

- Learners are given the opportunity to incorporate feedback into speaking and writing activities.

1 Take, for example, the following task for an ESL class focused on healthcare: “Respond appropriately to a patient’s concerns regarding an upcoming treatment.” Specific requirements could be included in instructions, such as “Be sure to introduce yourself professionally, break the ice, respond to questions and concerns, probe, check comprehension, provide information that is relevant to their concerns, reassure, and close the conversation appropriately.” These requirements could be converted to a rubric and used for self-, peer-, and instructor-evaluation.

2 Just living in an L2 environment may be considered an opportunity; however, instructors need to encourage participation in that L2 environment through, for example, tasks that require interaction with fluent speakers.

- Instructors have a deep understanding of the English grammar system and expertise in teaching grammar.

- The selection of which areas of grammar are explicitly taught in class is based on the following:

- The learners’ current linguistic competence (i.e., developmental stage, identified errors and gaps)

- The learners’ communication needs (e.g., related to tasks that they will perform)

- The curriculum

- The learners’ current linguistic competence (i.e., developmental stage, identified errors and gaps)

- Grammar instruction is integrated into skills/meaning-focused language teaching for the following reasons:

- To prepare learners for meaning-based communication tasks

- In response to learner error

- To prepare learners for meaning-based communication tasks

- Grammar instruction sometimes takes the form of isolated grammar lessons, especially related to the following structures:

- Those that occur infrequently

- Those that are difficult to perceive1

- Those that do not cause communication breakdown2

- Those that occur infrequently

- Connections are made between the form of a structure and its meanings and use.

- Grammar practice is contextualized within a task/theme/topic.

- Recognizing that it takes time for grammatical accuracy to develop, there is a spiralling of instruction; target structures are “recycled” into new topics, contexts, and tasks.

- Learners are introduced to resources that they can access to support their own grammar learning (grammar texts, websites, grammar checkers, etc.).

1 Thereby “helping learners notice language forms that occur frequently but are semantically redundant or phonologically reduced or imperceptible in the oral input” (Spada & Lightbrown, 2008, p. 195).

2 Those errors that do not interfere with meaning are less likely to be noticed. Isolated instruction may be necessary to encourage learners “to notice the difference between what they say and the correct way to say what they mean” (Spada & Lightbrown, 2008, p. 196–197).

- Learners are encouraged to pay attention to grammatical forms and form/meaning/use connections (i.e., awareness-raising tasks):

- In input (listening/reading)

- In output (speaking/writing)

- In input (listening/reading)

- Learners are encouraged to notice gaps and errors in their own use of grammatical forms.

- Learners receive ample exposure to target structures.

- Grammar instruction includes focused oral and written practice activities that range from very controlled to more open-ended so that learners can use their grammatical knowledge during meaning-focused communication.

- Grammar instruction goes beyond presentation and practice, ensuring that learners have opportunity to produce forms in meaning-focused communication.

- Learners receive corrective feedback in response to errors, for instance, through the following:

- Direct correction

- Clarification requests

- Elicitation of correct form

- Modelling the correct form, along with strategy training to increase awareness of the “reformulations”1 they encounter both inside and outside of class

- Direct correction

- Corrective feedback on learners’ grammatical errors occurs in a timely manner and ensures opportunity to incorporate that feedback in subsequent speaking and writing activities.

- Learners are encouraged to take responsibility for and manage their learning from corrective feedback by, for instance:

- Self-correcting and producing corrected forms (spoken and written)

- Recording and reflecting on the types and numbers of errors made in order to prioritize consistent or patterned errors

- Identifying and using online resources to address their own consistent or patterned errors

- Self-correcting and producing corrected forms (spoken and written)

1 These reformulations are often implicit. That is, NSs often incorporate a “corrected version” of what the learner said in their responses; often, however, learners fail to attend to these less explicit corrections.

- Pronunciation issues that affect intelligibility of learner speech are identified in the following ways:

- Formally through individual assessment

- Informally as miscommunications occur or as the instructor identifies pronunciation issues during communication tasks

- Formally through individual assessment

- Selection of what to teach related to pronunciation is based on the learners’ need to be understood:

- The first priority is speaking habits that affect intelligibility (e.g., mumbling, slurring, volume).

- The second priority is global issues (suprasegmentals) that affect intelligibility. These can include inappropriate sentence stress, syllable stress, intonation, and rhythm. These can also refer to problems related to unconnected speech, including addition of extra syllables and dropping of final consonants.

- The third priority includes those sounds (segmentals) that most affect intelligibility1, recognizing that most segments will improve on their own. Vowels are more important than consonants.

- The first priority is speaking habits that affect intelligibility (e.g., mumbling, slurring, volume).

1 Issues of intelligibility are affected by the “functional load” of a sound (including the frequency of the sound along with the relative abundance of minimal pairs involving the sound). A useful article on this issue is Brown (1988).

- Instructors have some expertise in phonology, the English sound system, and teaching pronunciation.

- Pronunciation instruction encourages awareness and analysis of the characteristics of spoken English (rhythm, intonation, sounds, stress, connectedness) in contrast to the visual/written forms of language. For instance, learners might do the following:

- Analyze and perceive target features in spoken language (e.g., in audio recordings, podcasts, videos, and in interactions outside the classroom)

- Identify useful rules/patterns (e.g., for the pronunciation of -ed endings)

- Engage in listening discrimination activities

- Learn how sounds are physically made

- Analyze and perceive target features in spoken language (e.g., in audio recordings, podcasts, videos, and in interactions outside the classroom)

- Pronunciation instruction provides opportunities for controlled practice, in which learners are focused primarily on form, for example:

- Perceptual exercises (perceiving the differences)

- Listening and repeating, mimicking

- Jazz chants, poems, rhymes, dramatic monologues, etc.

- Perceptual exercises (perceiving the differences)

- Pronunciation practice is focused on language that is familiar to learners (i.e., not obscure vocabulary) and contextualized (e.g., related to a text, theme, or task).

- Pronunciation instruction is integrated into regular classroom activities; it goes beyond presentation and practice and provides opportunities for instruction to be applied in communication, for instance:

- Using high-frequency formulaic sequences for pronunciation instruction and practice

- Practicing a particular pronunciation feature in preparation for a communication task (e.g., practicing the linking in phrases related to giving an opinion, or the word stress in a vocabulary list prior to a communication task requiring the use of those phrases/words)

- Simple information gap exercises targeting one pronunciation feature (e.g., rising intonation in Wh–questions)

- Communicative tasks that enable learners to use learned targeted pronunciation in fluency-focused activities (e.g., role-plays, dialogues, debates)

- Re-plays of communication tasks in which learners first do a communicative task with a focus on meaning and fluency, and then repeat the task with a focus on a particular pronunciation feature

- Using high-frequency formulaic sequences for pronunciation instruction and practice

- Pronunciation instruction enables learners to identify and perceive those issues in their own speech that cause problems with intelligibility, developing an ability to monitor their own pronunciation.

- Instructors are aware of and can guide learners in the use of technology resources to improve comprehensibility (e.g., voice recognition tools, voice recording tools, H5P Speak words, English Accent Coach).

- Instructors make principled decisions about what vocabulary to spend instructional time on. That is, instructors do the following:

- Highlight both familiar and new vocabulary

- Focus more on high-frequency (1K–2K) and mid-frequency (3K–4K) words

- Consider learners’ needs (e.g., words related to real-life needs; Academic Word List vocabulary for those learners continuing their education; occupation-specific words for learners headed to a particular kind of work)

- Consider relevance to the context (e.g., the listening/reading text; the task that learners will be doing)

- Use keyword and vocabulary frequency tools (see lextutor.ca)

- Highlight both familiar and new vocabulary

- Learners are encouraged to notice and focus on new words in a variety of ways:

- Explicit discussion of target vocabulary prior to listening, speaking, reading, or writing tasks (e.g., having learners search a text or listen for selected vocabulary items; having learners identify and discuss unknown vocabulary in a word cloud composed of words from the text)

- Lexical elaborations and textual enhancement in both paper and electronic readings (e.g., glosses, hyperlinks, underlining, bolding, italics)

- The incorporation of target vocabulary in pre-listening/reading activities to ensure multiple instances of item recall

- Highlighting of new vocabulary items as they come up (e.g., writing them on the board; encouraging students to write them in a vocabulary journal; adding them to a flashcard set)

- Presentation of new, thematically related items prior to a unit in which the theme is explored through a variety of activities and modes (e.g., Quizlets, H5P, and other interactive online activities that provide immediate feedback)

- Explicit discussion of target vocabulary prior to listening, speaking, reading, or writing tasks (e.g., having learners search a text or listen for selected vocabulary items; having learners identify and discuss unknown vocabulary in a word cloud composed of words from the text)

- Learners closely examine the form of the vocabulary items, for example:

- For words, learners count syllables, identify the stress pattern, notice word parts, spell, and pronounce the word in the context of common collocations.

- For formulaic sequences, learners analyze literal and figurative meanings; notice repeated sounds, linking, and stress patterns; and pronounce the sequence as a chunk.

- For words, learners count syllables, identify the stress pattern, notice word parts, spell, and pronounce the word in the context of common collocations.

- Learners connect form to meaning in a variety of ways:

- The use of visuals (pictures, sketches, Google image searches, realia, miming)

- Personalized anecdotes

- Quick L1 translations

- Instruction in and allowance for appropriate and judicious dictionary use (bilingual, monolingual, and bilingualized)

- Pairing of the use of clues (context, visual) to determine vocabulary meaning with the use of dictionaries, glosses, or group discussion to confirm guesses (to encourage retention of vocabulary)

- Opportunity to negotiate and discuss the meanings of target vocabulary (e.g., learners work in pairs or groups to figure out meanings of words/phrases or complete vocabulary activities; learners look up meanings and explain those meanings to others)

- The use of visuals (pictures, sketches, Google image searches, realia, miming)

- Learners identify common collocations, multiple uses, and grammatical variations of target vocabulary (e.g., through YouGlish, corpora searches, concept maps with lexical items and collocations, noticing collocations in written/spoken texts, and cloze activities).

- Vocabulary is presented in thematically related clusters (e.g., frog, green, pond), rather than in semantically related clusters (e.g., red, yellow, blue, green) that can cause confusion.

- Learners are provided with opportunities for maximum exposure to, engagement with, and retrieval of the target vocabulary and meanings, including a selection of the following:

- Manipulating or “doing something” with target vocabulary (e.g., sorting, matching, labelling pictures, filling in the blanks, completing crossword puzzles, and playing games where they retrieve target vocabulary based on pictures, charades, and/or definitions)

- Multimode exposure to target vocabulary in thematic teaching (listening, speaking, reading, writing)

- Narrow reading (reading a number of texts on a particular topic or by a particular author)

- Interactive online activities (e.g., Quizlet, H5P, Learning Chocolate)

- Vocabulary quizzes and tests

- Other

- Manipulating or “doing something” with target vocabulary (e.g., sorting, matching, labelling pictures, filling in the blanks, completing crossword puzzles, and playing games where they retrieve target vocabulary based on pictures, charades, and/or definitions)

- Learners are pushed to use target vocabulary in speaking and writing tasks, facilitating long-term retention, through, for instance:

- Explicit instruction related to content vocabulary and functional language prior to speaking and writing tasks

- Requiring the use of the target vocabulary in speaking/writing tasks (e.g., “Choose 3 of the new statements for expressing opinions and use them during the debate” or “Choose 8 of the new words to incorporate into your paragraph”)

- Disappearing text activities (e.g., where a text is on the board or projected, and learners read it aloud a number of times, with more and more target items deleted each time; or where a text is read aloud in its entirety, and then read aloud with pauses before target items so learners can fill in the pause orally)

- Encouraging learners to use new vocabulary in original (and potentially memorable) sentences

- Explicit instruction related to content vocabulary and functional language prior to speaking and writing tasks

- Learners are enabled to manage their own vocabulary learning through deliberate exposure to, instruction in, and sharing of vocabulary development strategies, such as the following:

- Strategies for identifying words to focus on

- Strategies for using the morphology of the word to make meaning/form connections (roots, affixes)

- Dictionary strategies (paired with guessing from context)

- Encoding and mnemonic techniques (e.g., relating a new word to existing knowledge as in the linking of an L2 word to an image or a sound-alike L1 word)

- Tools and strategies for recording targeted words (e.g., labelling pictures, creating electronic flashcards, creating physical flashcards, keeping a vocabulary notebook, drawing word webs, creating collocation tables)

- Moving from receptive retrieval (e.g., where students have to understand the word) to productive retrieval (where they have to elicit and use the word)

- Spacing repetition over a longer period (reviewing more often at the beginning, less often later on), as opposed to massed repetition (quick “cramming” for a vocabulary test)

- Strategies for eliminating boredom, and for encouraging and rewarding vocabulary learning1

- Strategies for putting new words to immediate use

- Apps and tools, such as Quizlet, LexTutor.ca, online dictionaries, word clouds, Learning Chocolate, YouGlish, etc.

- Strategies for identifying words to focus on

1 These strategies, which often involve pairing vocabulary learning with an activity a learner finds pleasurable, can be individual and innovative. For instance, learners have suggested the following strategies: going for a walk while reviewing flashcards; listening to music or eating a favourite snack while reviewing vocabulary; bouncing a ball while rehearsing; and creating a matching vocabulary game. Encourage learners to share the strategies that have worked for them.

For details on this best practice, see Best Practices for Technology and Online Learning.

- Instruction is sensitive to the cultural/religious norms of the learners.

- Instructors (as insider members of Canadian culture) mediate for learners the hidden culture of beliefs, values, and ways of knowing in Canada.1

- Classroom activities expand learners’ capacity to live and work in a multicultural environment by encouraging learners to do a selection of the following:

- Explore the impact of their own cultural assumptions on their own expectations, behaviours, choices, values, communication styles, etc.

- Explore the impact of the cultural assumptions of those they meet in Canada (e.g., in particular communities; in particular workplaces) on the expectations, behaviours, choices, values, communication styles, etc. of those individuals

- Reflect on their personal choice to acculturate/embrace an aspect of Canadian culture, or to preserve that aspect of their own culture

- Develop attitudes of curiosity, respect for other ways of being, and appreciation for diversity

- Notice, analyze, explore, reflect on, and engage with those instances where differences in cultural assumptions, expectations, behaviours, values, communication styles, etc. have resulted in dissonance, discomfort, or confusion. For instance, learners learn to brainstorm a variety of possible interpretations of a behaviour, rather than accepting the first (often negative) interpretation that comes to mind.

- Celebrate and share in a diversity of cultures and customs (e.g., through class presentations, celebrations of festivals and holidays, exposure to literature/art/music, performances, publishing of relevant writing assignments, discussions)

- Explore the impact of their own cultural assumptions on their own expectations, behaviours, choices, values, communication styles, etc.

1 The content and concept information which learners access through reading and listening activities is a vehicle or “carrier” of cultural information; part of the instructor’s role is to mediate, or “unpack,” this cultural information for learners.

- Learners are encouraged to take responsibility for their own learning by, for instance:

- Setting goals

- Developing strategies for self-assessment

- Using self-assessment checklists

- Documenting and reflecting on their own progress

- Maintaining a learning portfolio

- Taking responsibility for aspects of class management1

- Setting goals

- Instruction explicitly addresses learning strategies and provides opportunity for learners to practice and reflect on strategies.

- Learners develop an expanded repertoire of strategies for some of the following:

- Staying motivated

- Remembering and using new language

- Finding and expanding on opportunities to communicate2

- Increasing reading comprehension and speed

- Increasing writing fluency and accuracy

- Improving comprehensibility

- Other

- Staying motivated

- Learners use their language skills to access useful and meaningful interaction, knowledge, skills and services that allow them to be more independent and self-sufficient. This may include, for example:

- Using their electronic devices to access relevant information

- Participating in role-plays that transfer directly to real-life needs (e.g., role-playing a telephone conversation with a potential landlord)

- Completing tasks that mirror tasks required in real life (e.g., filling out a child’s field trip form or a workplace injury report)

- Using their electronic devices to access relevant information

- Learners participate in activities that prepare them for success in future academic endeavours, for example:

- Organizing learning materials

- Completing homework assignments

- Practicing academic skills such as note taking, outlining, and test taking

- Researching information and presenting research

- Learning and practicing critical thinking skills

- Giving oral presentations

- Organizing learning materials

- Learners make plans to continue learning once the class has ended.

1 For example, depending on the class, learners may take responsibility for organizing a social activity, planning a field trip, taking attendance, leading a discussion, orienting a new classmate, etc.

2 For example, non-verbal strategies for indicating a desire to communicate; strategies for opening a conversation; strategies for responding to compliments in ways that encourage rather than terminate a conversation.

Vignettes

This section includes descriptions of what the Best Practices might look like when applied in a variety of contexts.

Last fall, I was teaching a group of CLB 3 learners who were brand-new to Canada. My goal was to make sure that everything I did in the class was directly relevant to their real-life needs. I also wanted them to gain as much functional language as possible to speed up their ability to communicate. They needed to be able to talk to their children’s teachers. They wanted to be able to order food. Then winter hit, and they needed language to talk about and find winter clothing.

To help with learning functional language, I created Quizlets of vocabulary, but I had audios of functional language. For instance, a Quizlet with winter clothing had audios of someone saying “Hi, I’m looking for __” and the item pictured and written on the Quizlet (e.g., gloves, winter boots, scarf). Another Quizlet had pictures of clothing that was too big, too small, too tight, etc., and audios saying “I think this is too ___.” A Quizlet with fast foods pictured had audios of someone saying “Hi, I’d like to order ___” and the item pictured (a coffee, a burger, fries, etc.). A Quizlet about school messages had vocabulary such as “absent,” “late,” “leave early,” “not feeling well,” “doctor’s appointment,” etc. The audios said something like “Hello, I’m Sam’s mom. Sam will be absent today.” or “Hello, I’m Sam’s dad. Sam has a doctor’s appointment today.”

Students learned the vocabulary as they used the flashcards, learn, matching, and test Quizlet functions. They practiced sounding out and writing the words. At home and on the bus, they listened over and over to the functional language in the audios. As we role-played interactions in class, they used both the functional language and the vocabulary. In one activity, students sat in pairs, with one person facing the board and the other person facing away from the board. I would project a Quizlet picture or word (“gloves,” “burger,” “absent”), and the student facing the board would say “Hi, I’m looking for…” or “Hello, I’d like to order a…” or “I’m Sam’s mom. He will be…” and the other student would check their comprehension “gloves?” “a burger?” “absent?” and point to the item on a Quizlet printout. After a lot of practice and scaffolding, these real-life tasks became listening and speaking PBLA tasks that learners carried out to demonstrate progress.

Teaching employment-related English for CLB 3 and 4 students can be quite challenging. To ensure that students achieve their learning goals, I provide them with ample opportunity to practice their listening, speaking, reading, and writing skills.

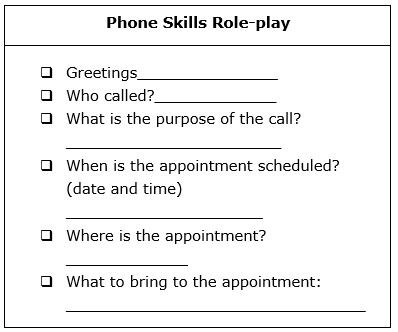

In one of my units, students develop their phone skills. First, they listen to sample phone calls from the LINC 3 audio files (e.g., Can I Take a Message? and Friendly Phone Conversation). Students listen to identify polite expressions and tone of voice. The audios are replayed 2–3 times and students write down details from each audio sample. Afterwards, they receive feedback on the details they captured. Then, students read a vocabulary chart containing phrasal verbs. They complete a worksheet on the meaning and usage of commonly used phrasal verbs related to phone calls ( e.g. “hold on,” “speak up,” “cut off,” etc.).

After this, students work with a partner and role-play phone conversations following the patterns they heard in the LINC 3 audios and using the phrasal verbs they learned. They demonstrate their role-plays for the class. This speaking activity builds students' confidence as they communicate with their classmates.

To reinforce what they have learned, I assign homework where students use a template to plan sample phone conversations with their doctors, dentists, counsellors, teachers, and many others. They write down the details they will need when making mock phone appointments with their classmates. Later, in class, students complete the same templates as they role-play the conversations with their classmates.

With all of this practice, my CLB 3–4 learners gain confidence in their listening and speaking skills, expand their vocabulary, and develop familiarity with reading and completing simple forms.

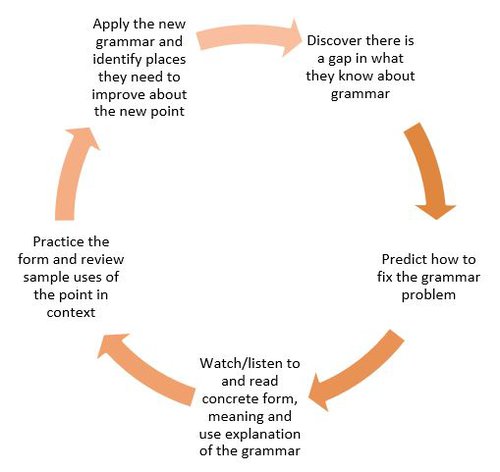

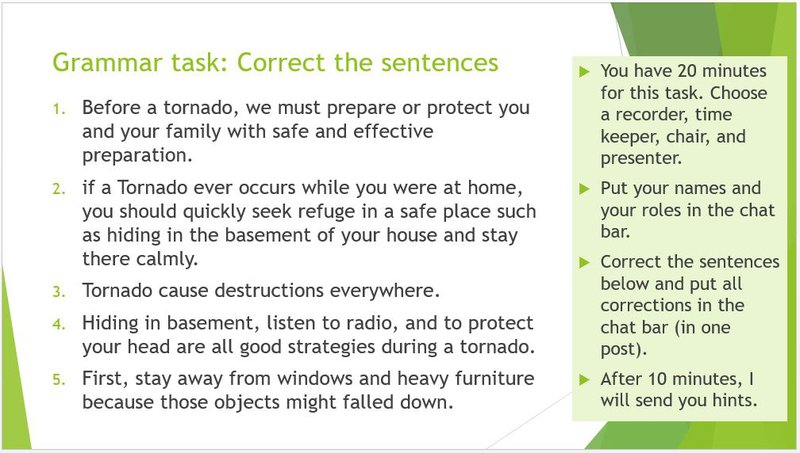

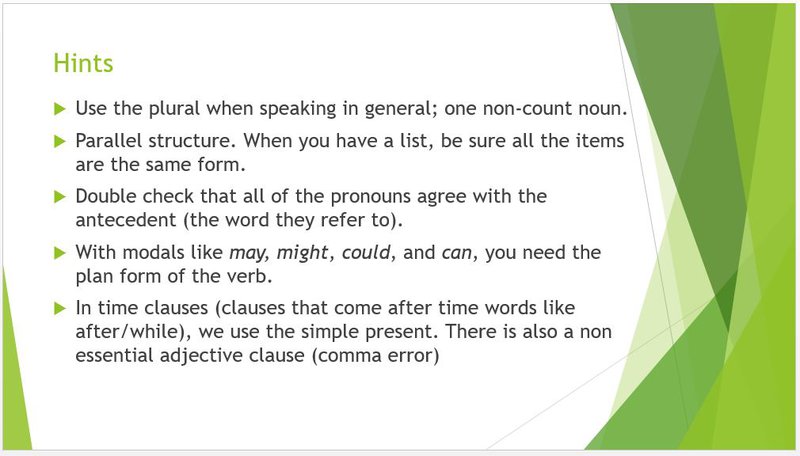

This year I have been trying a new routine that seems to be working for my grammar instruction. During the week I collect sentence errors that my learners commonly make. If my textbook treats a grammar point, I especially try to collect a few errors related to the point in the text.

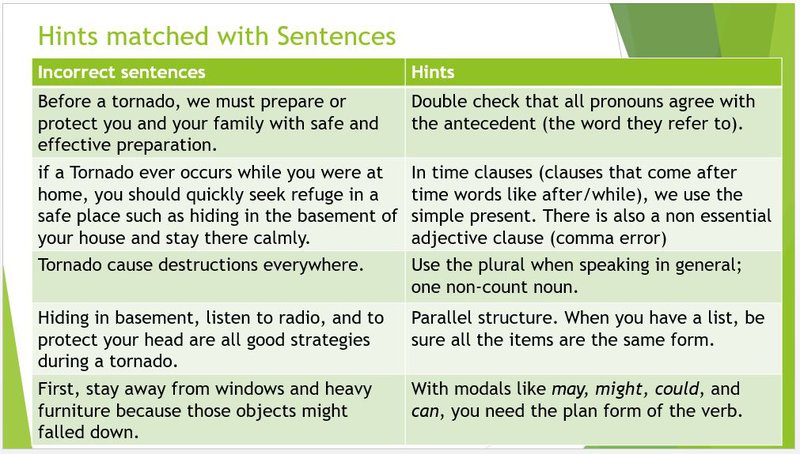

On Mondays, I present 5 sentences for error correction taken from a variety of anonymous learners. I break the learners into teams of 4, and I give each group the set of 5 sentences that have classic grammar errors. The teams work together to try to correct the sentences. After 10–15 minutes, I hand out a second sheet with hints for each of the 5 sentences, and learners have some time to apply the hints and adjust their corrections. Each group then presents their corrections on one sentence, and we discuss why these choices were made. After the discussion is over, I provide an answer key for their future reference.

For homework that night, I ask the students to read and review form, meaning, and use explanations related to one of the error sentences. I always provide a video and a written explanation because students seem to prefer one or the other. EngVid grammar videos and University of Victoria’s studyzone have been really good for my learners. I also have learners complete online activities with immediate feedback; I’ve found some great focus-on-form activities at Live Worksheets and British Council’s Learn English Teens.

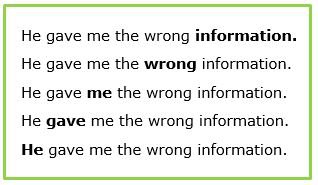

During the week that follows, we look for sample sentences in the textbook readings and in YouGlish. I use these to create cloze and fill-in-the-blank activities (very easy to do with H5P!). Near the end of the week we get into groups and write example sentences related to the topic of the week (often done as part of a prewriting/outlining activity).

Over the weekend the students do their formal writing assignment, and then on Mondays we repeat the cycle with a new grammar point. I integrate a couple of sentences that review the points we studied earlier. By the end of the term, we have recycled the grammar often enough that they seem to understand the form, meaning, and use of target structures, even if they still make small mistakes.

The sample slides below are from my CLB 7 class, but I think you could use this routine for CLB 3+ so long as the sentences are level-appropriate, and the grammar explanations are simple and easy to access.

I teach pronunciation remedially and in a targeted manner in almost all my classes. I also train teachers in pronunciation. I have found that most communication issues that occur in my classes are not based on content or meaning but rather on mode of communication. How a misunderstanding is approached or resolved can also be problematic depending on pronunciation issues. In many cases, pronunciation is the primary root of the problem. One ESL class that I was teaching was made up of two predominant language groups: Polish and Urdu speakers. The attitudes and atmosphere in the classroom were rocky in the beginning. There were a lot of misunderstandings based on pronunciation issues. The Eastern Europeans came across as bored and indifferent, while the South Asian speakers were perceived as arrogant and aggressive—neither of which was the intended meaning. I quickly addressed the situation, realizing that the issues were based on word focus and intonation. I did the following:

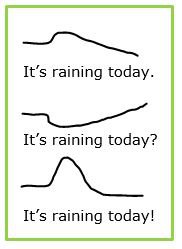

We started by looking at thought groups. I provided a couple of examples careful to emphasize the focus word: “Melica is standing.” “I love teaching.” “It’s raining today.” Students generated examples as a class, which I wrote on the board.

Then, we looked at the main word of each thought group and underlined the stressed syllable within each thought group, depending on the context of the statement. I gave the students a rubber band to use to show the focus word in each thought group by extending the rubber band on the stressed syllable of the focus word: Melica is standing. I love teaching. It’s raining today.

Next, I drew the intonation contours over each thought group, showing how in English we rise on the stressed syllable of the focus word and then fall gently and not sharply. I also mimicked intonation patterns that had been used in the class to show how perceptions can convey different meanings in English, focusing on aggressive and indifferent patterns in English. I emphasized that while these are the perceptions in English, in other languages they may be seen as normal. The key is to be aware of the message being relayed when transferring L1 intonation patterns to English because they may not convey the intended meaning and may, therefore, result in miscommunication.

We practiced using the thought groups generated on the board at the beginning of the class and manipulated the focus words to show how the meaning can change. I also provided the following sentences to show how this can change the meaning and the knee-jerk, reflexive perceptions that are conveyed.

We practiced controlled dialogues asking for clarification in situations that arise from miscommunication.

Lastly, we practiced role-plays, focusing on fluency, with similar situations as in #5, emphasizing language and strategies that can be used to diffuse difficult situations.